Philosophy Before Framework

Most organisations struggle less with execution than with decision quality.

Teams work hard. Frameworks are adopted. Tools improve. Yet effort still fails to translate cleanly into outcomes.

For technology leaders, the issue is often not what is being done, but how decisions are being made about the work in the first place. Without clarity on intent and context, methodologies are applied inconsistently and tools are expected to compensate.

This article explores a simple but powerful distinction—philosophy, methodology, and tools—and why understanding the order between them materially improves decision-making, adaptability, and results.

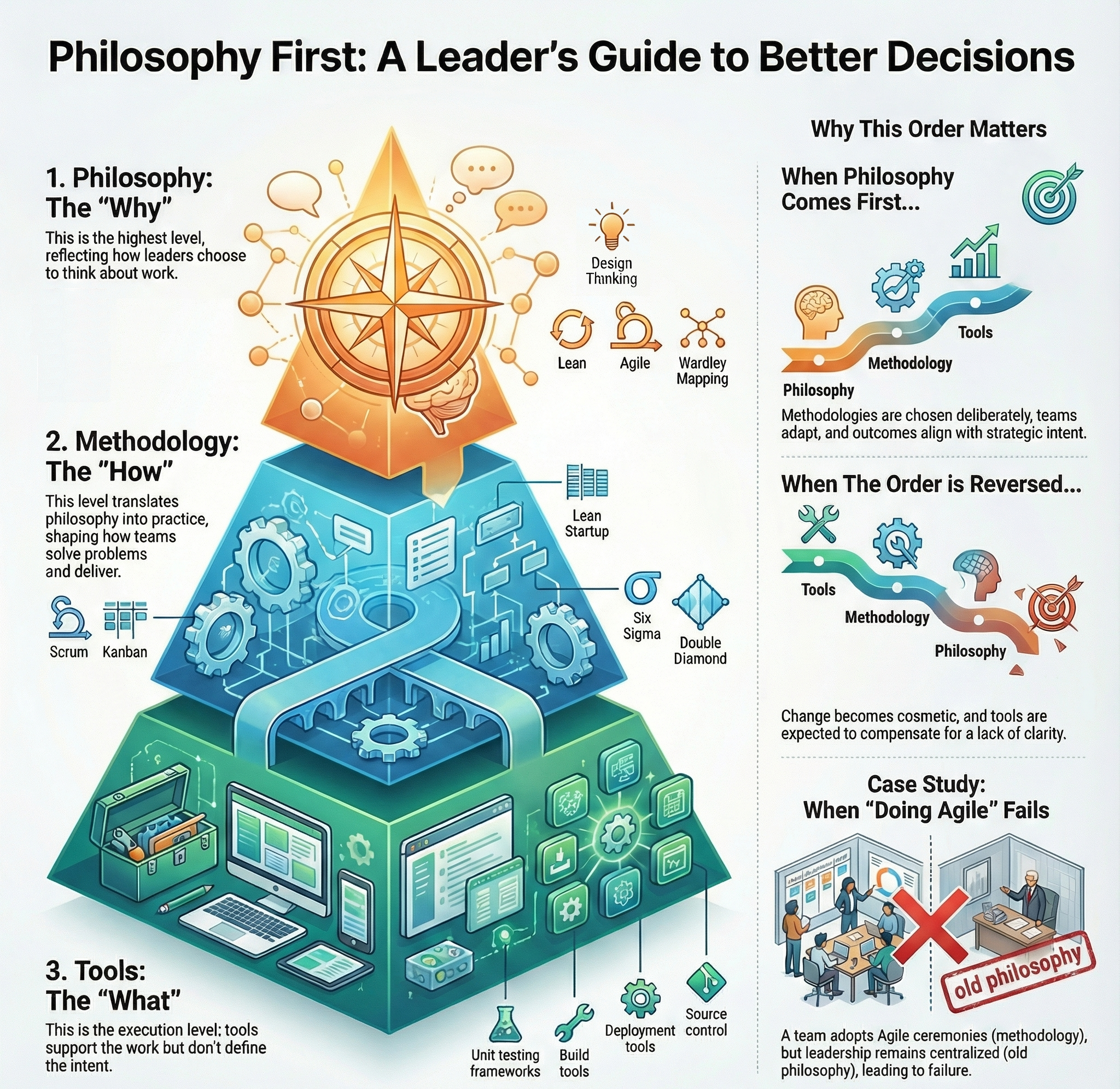

Philosophy → Methodology → Tools

When this order is reversed, change becomes cosmetic. When it is respected, operating models become easier to adapt.

Philosophy: how leaders choose to think about work

Philosophy sits at the highest level.

It reflects how leaders interpret uncertainty, value, risk, and change. Importantly, mature organisations do not operate under a single philosophy. They draw from several, depending on context.

Common philosophical lenses include:

- Lean thinking, focused on value, flow, and waste

- Design thinking, focused on discovery and customer need

- Agile thinking, focused on learning under uncertainty

- Wardley Mapping, focused on situational awareness and evolution

These are not competing belief systems. They are complementary ways of understanding different types of work.

The strategic role of the CIO is not to mandate one philosophy, but to recognise which lens best fits the problem at hand.

Methodology: how philosophy is applied

Methodologies translate belief into practice.

They shape how teams explore problems, make decisions, and deliver outcomes. Crucially, methodology should change as the nature of the work changes.

Examples include:

- Scrum or Kanban

- Lean Startup

- Waterfall

- PDCA

- Six Sigma

- Double Diamond

When philosophy is clear, methodology becomes a choice rather than a default. Leaders stop asking “what framework should we use?” and start asking “what approach fits this problem, right now?”

Tools: how work is executed

Tools sit at the lowest level.

They support execution but do not define intent. Tools reflect decisions already made upstream.

Used well, tools reinforce behaviour. Used poorly, they amplify confusion.

Two Practical Examples

Example 1: Discovery work versus core systems

An organisation wants to improve its customer ordering experience while also stabilising its ERP.

At a philosophical level, these are different problems.

The customer experience work involves uncertainty, behaviour, and learning. Design and Agile philosophies are appropriate, supported by experimentation and fast feedback.

The ERP work demands predictability, control, and risk management. Lean, structured delivery, and formal change practices make more sense.

The mistake is not choosing one approach over the other. The mistake is applying the same methodology and governance to both.

Strategic leadership shows up in making this distinction explicit.

Example 2: When “doing Agile” fails

A leadership team mandates Agile across all technology teams.

Ceremonies are introduced.

Backlogs are created.

Stand-ups appear on calendars.

Yet decision-making remains centralised. Risk tolerance does not change. Teams are still measured on utilisation and delivery dates.

The methodology has changed.

The philosophy has not.

Without a belief in learning, autonomy, and outcome-based accountability, Agile rituals become a new wrapper around old behaviours. This is why many transformations stall without an obvious point of failure.

Why This Matters for CIOs

For CIOs seeking to move beyond being an order taker, this distinction is foundational.

Many of the behaviours associated with strategic leadership—focusing on outcomes, adapting approach, managing flow—are not techniques. They are expressions of underlying beliefs about how work and value creation actually happen.

Frameworks such as Cynefin help leaders recognise the nature of the problem. Philosophy determines how they respond once that recognition occurs.

The Executive Takeaway

Becoming a strategic leader is not about committing the organisation to a single way of working.

It is about developing the judgement to apply the right philosophy, select an appropriate methodology, and support it with fit-for-purpose tools.

When philosophy is clear:

- methodologies are chosen deliberately

- tools are easier to rationalise

- teams adapt instinctively

- outcomes align more closely with intent

That is what sustainable agility looks like at an executive level.

Not speed for its own sake, but the ability to choose the right response as conditions change.