Contradictions of a CIO

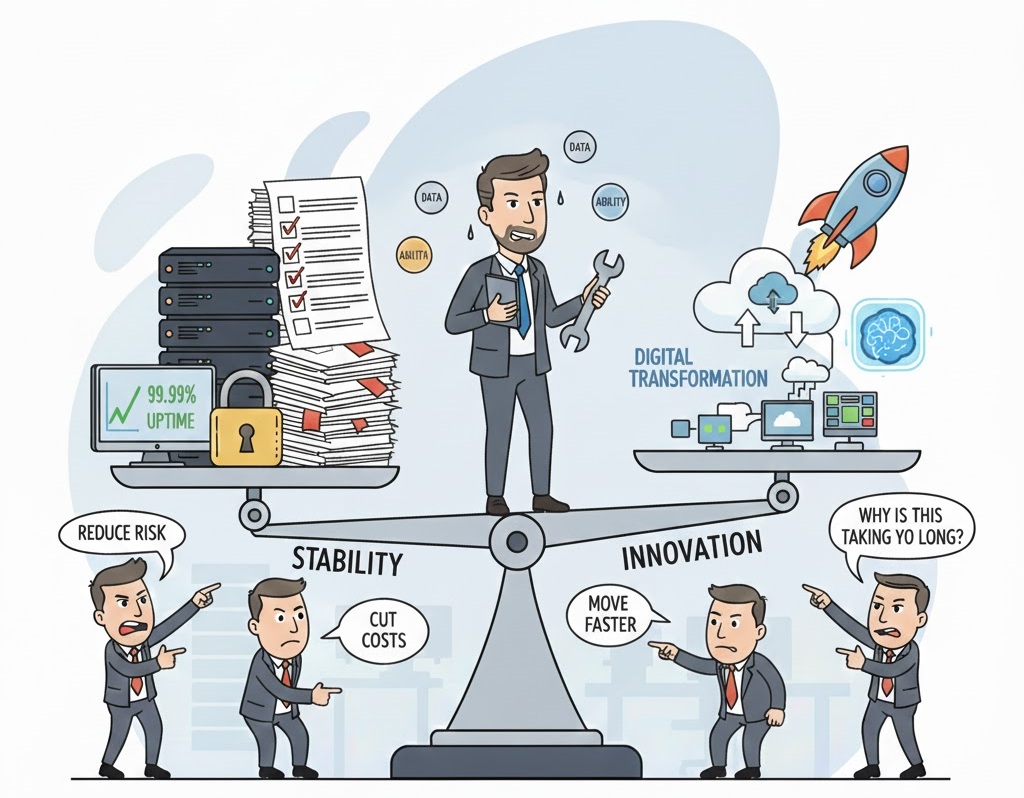

Described in the “CIO Paradox: Battling the Contradictions of IT Leadership”, Heller explains how the expectations of an IT leader can be contradictory to one another.

For example, we are expected to distrupt, but manage risk. Consolidate, but grow. Move fast, but provide reliability.

This is not unique to technology leadership. Finance balances cost control with investment. Operations balances efficiency with resilience. Every executive role lives with trade-offs. What is slightly different for technology is the persistence of decisions. Platforms, architectures, and operating models tend to stay in place for years. Reversing them is possible, but rarely quick or cheap. That gives technology choices a longer tail of impact across cost, risk, and flexibility.

This is where the CIO role becomes less about choosing sides and more about judgement. The job is not to eliminate tension, but to manage it deliberately as the organisation grows, scales, and resets priorities.

To understand this better, consider the five core CIO paradoxes.

The Five Paradoxes of the CIO Role

The Innovator’s Dilemma

The CIO is expected to keep systems stable, secure, and predictable, while also pushing the organisation toward new technologies and ways of working. Stability rewards caution; innovation rewards risk. In practice, this means running production environments that cannot fail, while experimenting with tools that, by definition, might. The tension shows up in funding, timelines, and tolerance for disruption. The CIO’s job is not to choose one over the other, but to create safe boundaries where innovation can happen without putting day-to-day operations at risk.

The Business–IT Alignment paradox

CIOs are expected to be deep technical experts and fluent business leaders at the same time. Too technical, and they are seen as disconnected from strategy. Too commercial, and they are seen as lacking credibility with engineers and vendors. Strategic alignment depends on understanding how revenue is made, where margin is created, and what risks matter most, while also knowing what is technically feasible, scalable, and sustainable. This is less about translating IT into business language, and more about making technology decisions that directly support commercial goals.

The Digital Literacy paradox

CIOs are often held accountable for technology outcomes, while other executives make technology-shaped decisions without understanding the consequences. Choices about speed, cost, security, or scope can look simple on the surface, but carry long-term implications for risk, scalability, and operational load. When digital literacy is low, technology is treated as interchangeable or instant, rather than as an interconnected system. The paradox is that CIOs must respect executive decision-making authority, while also preventing decisions that quietly create future constraints, cost, or failure. This is not about saying “no”, but about making trade-offs visible before they become problems.

The Influence paradox

CIOs are expected to deliver outcomes, but often lack the authority to make the decisions required to achieve them. IT is frequently positioned as a service provider or overhead, rather than a strategic function, which limits formal decision rights. Progress relies on influence: building trust, shaping priorities, and aligning stakeholders who do not report to IT. The paradox is that the CIO must lead change across the organisation, without being able to mandate it. Leadership here is measured by outcomes achieved through collaboration, not control.

The Blame paradox

CIOs are asked to accept accountability for project outcomes, even when they do not control scope, funding, timelines, or key decisions. This is often caused by projects being defined in terms of outputs rather than outcomes: deliver the system, migrate the data, go live on the date. When the business outcome falls short, accountability shifts to IT. The paradox is that CIOs are responsible for results, but constrained by decisions made elsewhere. Managing this requires clarity on ownership, explicit articulation of risks, and, occasionally, reminding everyone that delivering exactly what was asked for is not the same as delivering what was needed.

Embracing the Paradox

CIOs operate at the centre of these paradoxes, and that is where the role delivers its greatest impact. Balancing stability with progress, commercial outcomes with technical reality, and influence with accountability is not a contradiction to be solved, but a capability to be developed.

For CIOs, the opportunity is to lean into the tension:

- Use it to surface clearer trade-offs

- Turn competing priorities into informed decisions

- Translate complexity into direction the organisation can act on

For executives, these paradoxes provide useful context for technology leadership:

- Why speed, cost, and risk must be balanced, not maximised

- Why early engagement leads to better outcomes

- Why shared ownership produces more durable results

Many CIOs have felt these tensions instinctively, even if they did not have language for them. Recognising the paradoxes brings clarity, confidence, and alignment. When these tensions are acknowledged and navigated deliberately, technology leadership becomes clearer, more effective, and better aligned with organisational goals.

Reference

Heller, M. (2019). The CIO Paradox: Battling the Contradictions of IT Leadership. Greenleaf Book Group.